“Papillary heads optimization” for more geometric repair of functional mitral regurgitation toward ventricular treatment

Introduction

In the era of structural heart disease where catheter-based treatment is prevailing, surgery may have a unique role. For example, surgery may be potentially advantageous in functional mitral regurgitation (FMR), a ventricular disease that not only needs valvular treatment but also requires a ventricular intervention. Being stimulated by the innovative work by Kron et al. (1), we reported anterior relocation of papillary muscles and showed that it improves LV function and FMR (2,3). The revised version [i.e., papillary heads optimization (PHO)] can ameliorate tethering of both anterior and posterior leaflets (4).

Since PHO surgery is a little complex, here we provide information of safeguards and pitfalls.

Surgical safeguards, pitfalls and comments

Identification of properly-indicated patients

During the surgery, careful inspection of the valve and subvalvular apparatus is important. Tethered leaflets and dislocated papillary heads can be repairable but thickened or shortened leaflets or chordae may not be. Variation in papillary muscles may make surgery less effective, as will be described below.

Papillary muscles and their heads

When a patient has papillary muscles of normal or typical structure [i.e., a couple of heads arising from the anterior papillary muscle (APM) and a few heads from the posterior papillary muscle (PPM)], PHO is well indicated.

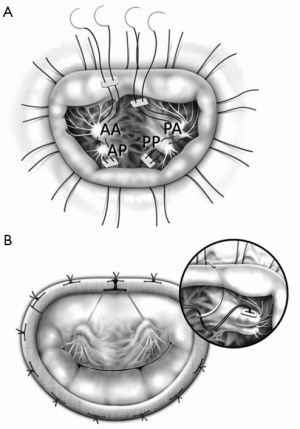

In such cases, we place polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sutures to the posterior head of the PPM, put it through the anterior head of the PPM and then tie the suture to stabilize the papillary heads complex (4) (Figure 1A).

Care should be taken to avoid tearing the muscle when the papillary head, especially the posterior head, seems thin and fragile; in such cases, we recommend putting the suture in a more proximal part of the papillary heads.

All the above procedures are done deep inside the left ventricle. Therefore, chordae tendineae and thebesian blood may interfere with them. We recommend using MICS instruments which have a long arm and small tip. In addition, the PPM heads are more difficult to see and so we place annuloplasty sutures first, which improves exposure of the PPM.

When the P2 segment is supported by a small independent papillary muscle which directly arises from the posterior LV wall, one cannot necessarily connect the papillary head to the anterior segment as it may tear the papillary muscle. In such cases, we recommend patch augmentation of the P2 segment or placement of artificial chordae from the anterior PPM head to P2.

Natural chordae tendineae

Using the PTFE sutures, we resuspend them to the mid-anterior annulus (Figure 1B). It is important to avoid hooking the sutures with natural chordae.

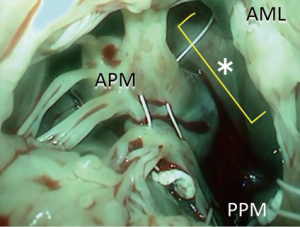

We bring the sutures via the midline of the mitral valve where chordae are almost completely absent, which provides enough space to work in (Figure 2).

Mitral annulus

We place the PTFE suture through the mid-anterior annulus from the ventricular side to the atrial side. This step is often regarded as difficult; if the suture goes too close to the aortic valve, it may cause aortic regurgitation, and if it goes to the leaflet side, it may cause mitral regurgitation or tissue tear. In order to avoid such complications, we put the suture just 1-2 mm away from the annuloplasty suture on the leaflet side. Since the suture will be connected to the ring in the next step, it will not distort the leaflet shape.

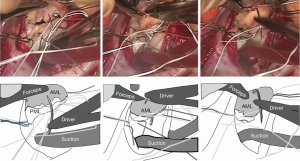

When the needle does not reach the annulus easily, we use a large French-eye needle which makes the procedure easier. A potential hazard of using such a big needle is that it can reach or hit the aortic valve more easily. Thus, we use a step-by-step approach; we handle the big needle just to ‘touch’ the middle of the anterior leaflet which is usually visible and then bring it a couple of mm toward the annulus, touching the leaflet again. By repeating the procedure, we can safely reach the target point (Figure 3).

Annuloplasty ring

After putting the annuloplasty sutures through the ring, we put the ring down to the annulus. We placed the PTFE sutures through the ring and after adjustment of the suture tension/length, we tied them up.

However, sometimes the PTFE sutures were cut by the metal inside of the ring. Moreover, the friction between the suture and the ring material may make the tension control inaccurate. Therefore, we put the PTFE suture around (not through) the ring and tie it after tension adjustment.

Tension/length control of the PTFE sutures

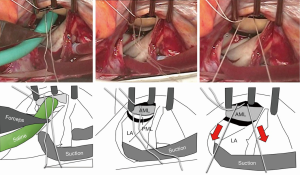

The most reproducible method of tension control is to put the suture via the aortic curtain to outside the heart, and later to adjust the tension under the guidance of transesophageal echo after terminating cardiopulmonary bypass. Since this method is time consuming, we often use an alternative approach. We infuse saline into the LV via the left atrium (i.e., the standard saline test) and then pull the PTFE sutures until we see some prolapse toward the left atrium. The sutures are subsequently tied (Figure 4). After coming off the cardiopulmonary bypass, the above prolapse is neutralized by the preoperative tethering.

Conclusions

By careful patient selection and handling of sutures and subvalvular apparati, PHO can be performed without complications. It may help patients with FMR as both valvular and ventricular treatment.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kron IL, Green GR, Cope JT. Surgical relocation of the posterior papillary muscle in chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:600-1. [PubMed]

- Fukuoka M, Nonaka M, Masuyama S, et al. Chordal “translocation” for functional mitral regurgitation with severe valve tenting: an effort to preserve left ventricular structure and function. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:1004-11. [PubMed]

- Masuyama S, Marui A, Shimamoto T, et al. Chordal translocation: secondary chordal cutting in conjunction with artificial chordae for preserving valvular-ventricular interaction in the treatment of functional mitral regurgitation. J Heart Valve Dis 2009;18:142-6. [PubMed]

- Komeda M, Koyama Y, Fukaya S, et al. Papillary heads “optimization” in repairing functional mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1262-4. [PubMed]