Performance of the Cox Maze procedure—a large surgical ablation center’s experience

Overview

Our cardiac surgical program performs 1,200 cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) procedures annually with approximately 100-120 [50% of patients who present with atrial fibrillation (AF)] of these patients undergoing an AF surgical ablation (SA) procedure concomitant to their cardiac surgical operation. Furthermore, we also perform stand-alone surgical ablation for AF as an isolated procedure for patients that are either referred or have chosen to have surgical ablation. Our ablation program was started in late 2005. To date we have performed over 800 SA procedures with the Cox Maze III/IV procedure as the procedure of choice in over 80% of the SA procedures (1-4).

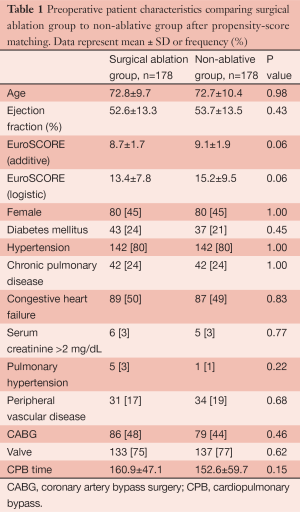

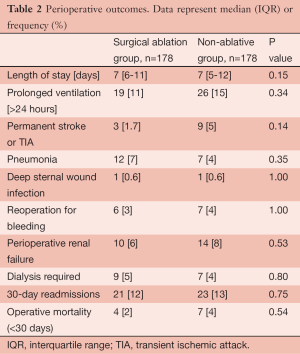

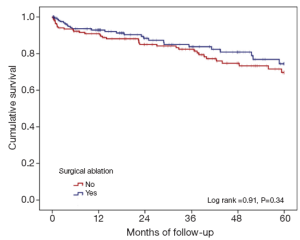

The large and diverse cardiac surgical program gives rise to the opportunity to perform SA procedures in high risk patients with very acceptable and reasonable results. In one published report, we discussed our results for patients considered high risk (Additive EuroSCORE >6). Using data from our local Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgical Database (STSACSD) and our unique AF registry, we propensity-score matched patients who underwent a SA procedure to patients with AF who did not undergo an ablative procedure (n=178 per group). This study suggested that the addition of SA to a high risk case did not result in a higher complication rate but did result in a higher rate of five-year cumulative survival (74.4% vs. 69.7%) (Tables 1,2 and Figure 1). We concluded that high surgical risk should not be the only decision factor when evaluating a patient for SA (5).

Full table

Full table

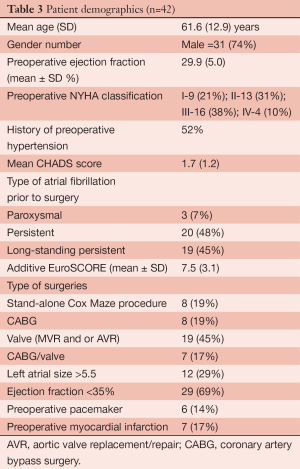

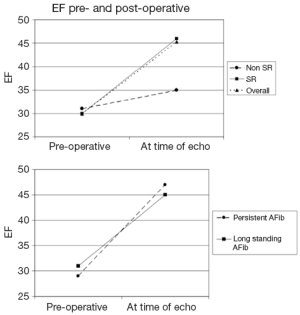

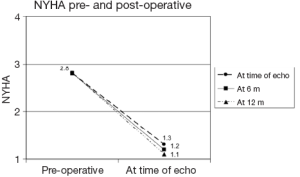

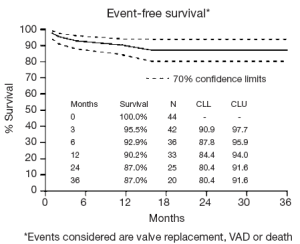

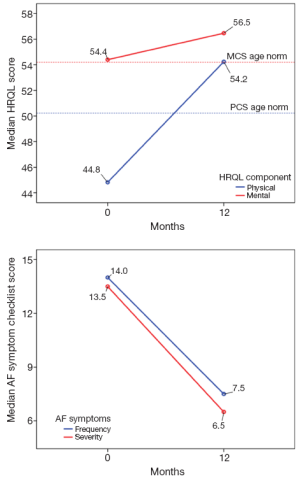

We have also studied the performance of SA in a subset of high risk patients, those with low ejection fractions (6). In this study we had complete follow-up on 42 patients who met the criteria of low ejection fraction, heart failure and AF (Additive EuroSCORE 7.5±3.1). We determined in this unique high risk group that SA was performed safely and effectively. Our conclusion was based on the following results: a return to sinus rhythm rate of 86% at the time of their follow-up echo; an improvement of the average ejection fraction from (30±5.0)% to (45±13.0)%; a significant decrease in the NYHA classification from an average of 2.8 to 1.1 at the time of the echo; a significant increase in patients’ self-report of their health-related quality of life physical functioning scores, which surpassed the national norms for people living with heart disease, as well as a significant decrease in their reported AF symptom burden and an event-free survival of 87% at two years (events considered were valve replacement, VAD or death) (Table 3, Figures 2-4) (6).

Full table

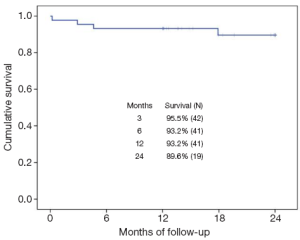

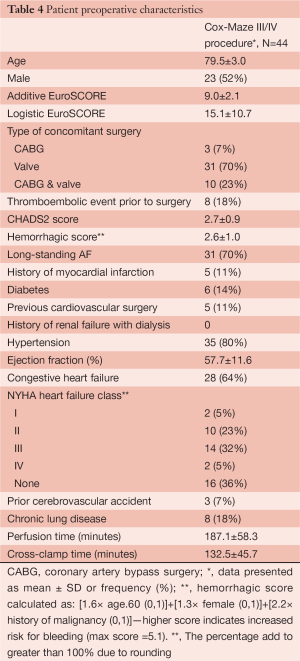

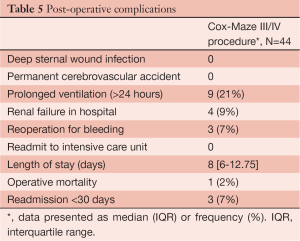

Older age is a significant deterrent to performing an additional surgical procedure, even though patients over the age of 80 years have a 1 in 9 chance of developing AF in their lifetime. In addition, patients are now presenting to cardiac surgery older, and in many cases sicker (7-10). Therefore, we studied another subset of high risk patients, those over the age of 75 who presented to cardiac surgery with AF. At the time of this study, we had 44 patients who met the inclusion criteria of being over the age of 75 years old and undergoing a full Cox Maze III/IV procedure (7). The average age for this population was 79.5±3 years with a mean additive EuroSCORE of 9±2.1 (very high risk). The majority (93%) of the patients underwent a concomitant valve procedure (Tables 4,5). The rate of return to sinus rhythm at 6 and 12 months was 90% and 85% respectively. Two year cumulative survival was 89.6% and there were no embolic strokes or major bleeding incidents in this group (Figure 5). We again concluded that advanced age alone should not be a discriminating factor when considering whether to perform the Cox Maze III/IV procedure.

Full table

Full table

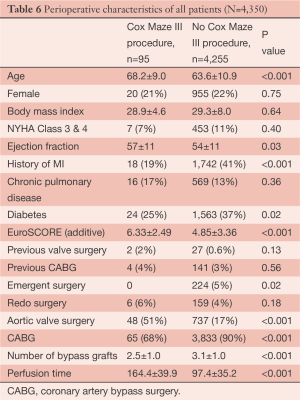

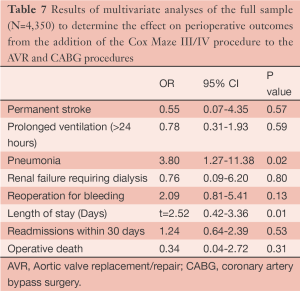

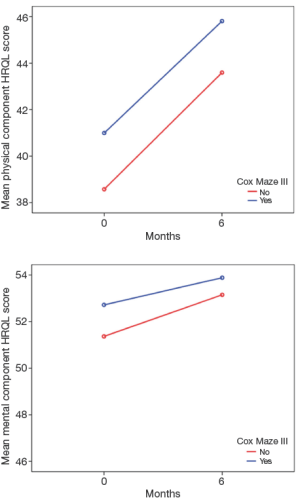

Aortic valve replacement/repair (AVR) and coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) are two of the most common surgeries performed. However, patients who have AF and are undergoing these surgical procedures are less likely to have a SA procedure performed (11,12). Therefore, we investigated whether operative risk was increased when adding the Cox Maze III/IV procedure to AVR or CABG surgery (13). Using propensity-score matching, we matched 95 patients who underwent a full Cox Maze III/IV procedure concomitant to an AVR, CABG and AVR/CABG procedure (Cox Maze III/AVR =30; Cox Maze III/CABG =47; Cox Maze III/AVR/CABG =18) to patients without a history of AF but underwent an AVR, CABG or AVR/CABG procedure. There were no differences between groups in perioperative outcomes except that the Cox Maze group was on CPB longer and had more pacemakers implanted. However, survival was not different between the groups in a mean follow-up of 35 months. The Cox Maze group had a return to sinus rhythm rate of 94% with 81% off Class III anti arrhythmic medications by 12 months, and both groups had significant improvement in their reported health-related quality of life (13) (Tables 6,7 and Figure 6). This study is of importance as less than 30% of the patients who presented to surgery with AF and these concomitant pathologies are being offered SA in North America. This is despite the data suggesting that leaving the patients in AF is associated with lower long-term survival and higher morbidity that is mainly associated with Coumadin and embolic events (12,14). We concluded that the Cox Maze procedure should be considered in patients who present for cardiac surgery in AF and will undergo CABG and or AVR procedure.

Full table

Full table

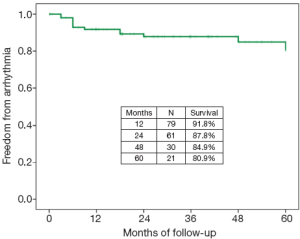

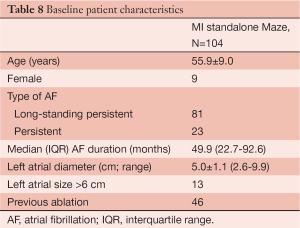

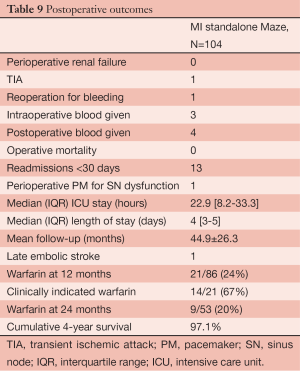

A unique aspect of our program is that patients have the opportunity to undergo the full Cox Maze procedure through a minimally invasive approach. In a recent report, we shared the results of patients who underwent a stand-alone minimally invasive procedure for non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (15). Using a small right mini-thoracotomy incision (6 cm) and femoral cannulation and fibrillating heart with no cross clamp, a full Cox Maze III/IV procedure was performed on 104 patients at the time of the study. This population was younger, with a mean age of 55.9±9.0 years, the vast majority of the patients being male (91%), and 78% having long-standing persistent AF. Almost half of the patients had undergone at least one percutaneous catheter ablation prior to their SA. The left atrial size was significantly higher than normal (average left atrium size was 5.0±1.1 cm). The return to sinus rhythm rate was >90% at all time points through to the last follow-up of 36 months (6, 12, and 24 months), with at least 80% off anti-arrhythmic drugs at each time point respectively. A longer duration of AF was a predictor of failure of the procedure. Arrhythmia-free survival for the first five years after surgery was 81% (Figure 7). Patients reported a significant increase in their health-related quality of life, especially when compared to age group national norms (Tables 8,9 and Figure 8). However, we did discern that there was a significant learning curve associated with performing a minimally invasive Cox Maze III/IV procedure after observing that our return to sinus rhythm at one year went from 89% for the first 20 patients to 94% for the remaining patients. Based on these results, we concluded that the Cox Maze procedure can be performed safely and effectively in this very challenging group of patients. However, there is a significant learning curve associated with performing this procedure, and therefore emphasis must be placed on educational opportunities for surgeons to master this technique (15).

Full table

Full table

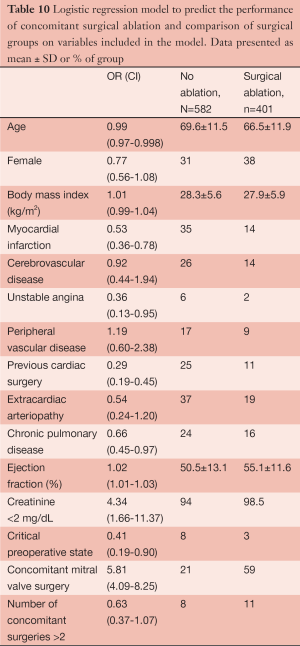

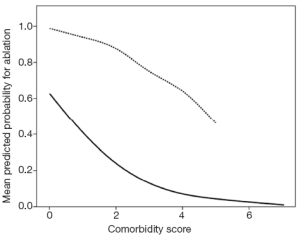

All of the studies presented thus far have demonstrated that the Cox Maze III/IV procedure, in contrast to misperception among many surgeons and cardiologists, can be performed very safely and effectively in a wide group of patients. They furthermore suggests that each patient who presents for cardiac surgery while experiencing AF should be evaluated on an individual basis and not just on rote criteria. To investigate this point more thoroughly, we conducted an analysis of our data to determine the impact of clinical presentation and surgeon experience on the decision to perform SA, since our program has multiple surgeons (n=8) who perform AF surgical ablation (16). Overall, we found that the rate of performing SA significantly increased from 31% in 2005 to 49% in 2010 (PTable 10, Figure 9). Surgeon experience was also a predictor, such that there was a 6% greater chance of having SA procedure for every 10 SA cases performed. Surgeons who had ablated >50 patients ablated 57% of the AF patients, while those with 12).

Full table

Summary

This brief discussion has covered only several of our published manuscripts on our work with patients who have undergone a SA procedure. However, the papers we chose to present were chosen to help demonstrate that SA can be performed safely and effectively even in the most high risk patients. It is our hope that through this discussion, the percentage of patients who are offered and undergo an AF ablative procedure will increase from the current figure of only 38% (11). However, we feel in order for this increase to occur, there must be a comprehensive approach to educate and train surgeons so that the safety and integrity of the SA procedure will be maintained.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cox JL, Schuessler RB, D’Agostino HJ Jr, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. III. Development of a definitive surgical procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;101:569-83. [PubMed]

- Cox JL. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. IV. Surgical technique. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;101:584-92. [PubMed]

- Cox JL, Boineau JP, Schuessler RB, et al. Modification of the maze procedure for atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. I. Rationale and surgical results. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;110:473-84. [PubMed]

- Cox JL, Jaquiss RD, Schuessler RB, et al. Modification of the maze procedure for atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. II. Surgical technique of the maze III procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;110:485-95. [PubMed]

- Ad N, Henry LL, Holmes SD, et al. The impact of surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation in high-risk patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:1897-903; discussion 1903-4.

- Ad N, Henry L, Hunt S. The impact of surgical ablation in patients with low ejection fraction, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;40:70-6. [PubMed]

- Ad N, Henry L, Hunt S, et al. Results of the Cox-Maze III/IV procedure in patients over 75 years old who present for cardiac surgery with a history of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2013;54:281-8. [PubMed]

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001;285:2370-5. [PubMed]

- Chugh SS, Blackshear JL, Shen WK, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of atrial fibrillation: clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:371-8. [PubMed]

- Deschka H, Schreier R, El-Ayoubi L, et al. Prolonged intensive care treatment of octogenarians after cardiac surgery: a reasonable economic burden? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013;17:501-6. [PubMed]

- Gammie JS, Haddad M, Milford-Beland S, et al. Atrial fibrillation correction surgery: lessons from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Cardiac Database. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:909-14. [PubMed]

- Ad N, Suri RM, Gammie JS, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation trends and outcomes in North America. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:1051-60. [PubMed]

- Ad N, Henry L, Hunt S, et al. Do we increase the operative risk by adding the Cox Maze III procedure to aortic valve replacement and coronary artery bypass surgery? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:936-44. [PubMed]

- Bando K, Kasegawa H, Okada Y, et al. Impact of preoperative and postoperative atrial fibrillation on outcome after mitral valvuloplasty for nonischemic mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:1032-40. [PubMed]

- Ad N, Henry L, Friehling T, et al. Minimally invasive stand-alone cox-maze procedure for patients with nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:792-8. [PubMed]

- Ad N, Henry L, Hunt S, Holmes SD. Impact of clinical presentation and surgeon experience on the decision to perform surgical ablation. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;96:763-8. [PubMed]