Pivotal contemporary trials of percutaneous coronary intervention vs. coronary artery bypass grafting: a surgical perspective

Introduction

Since its introduction in 1968, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been the gold standard of coronary revascularization for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). In 1977, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was introduced as an alternative coronary revascularization strategy. Advances in CABG, such as better and less invasive operative techniques, perioperative care, use of arterial conduits, and enhanced myocardial protection have significantly reduced the mortality and morbidity associated with CABG. Concomitantly, the evolution of newer generations of stents and improvement of techniques have made PCI feasible for treating complex coronary lesions. As a result, several sizable RCTs have been conducted to evaluate whether PCI is as good as CABG for patients with CAD.

RCTs comparing CABG vs. PCI [2005–2015]

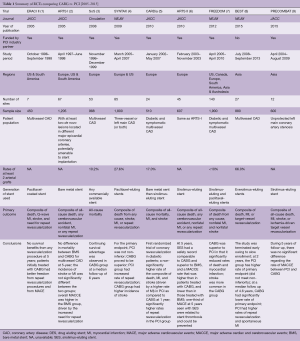

We have summarized the major multicenter RCTs comparing CABG vs. PCI published between 2005–2015 (1-9) (Table 1). Virtually each of these trials had been undertaken to demonstrate non-inferiority of PCI as compared to CABG. Several overarching conclusions were drawn: (I) CABG yielded superior survival outcomes in long-term follow up (3,7); (II) CABG led to lower rates of MACE/MACCE (1,2,4,6,8); (III) PCI group had higher rates of repeat revascularization (1,2,4-6,8). However, stroke was more likely to occur with CABG (4,7). Based on these findings, CABG continues to remain the intervention of choice for those needing coronary revascularization.

Full table

EXCEL and NOBLE: patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease (ULMCA) stenosis

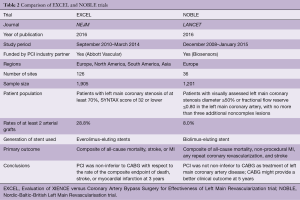

Whether CABG vs. PCI was the optimal revascularization strategy in patients with ULMCA stenosis again became a topic of heated debate in 2017, due to the simultaneous publication of the EXCEL (10) and NOBLE (11) randomized trials. A table summarizing these 2 contemporary RCTs is provided in this perspective (Table 2). These two studies yielded different conclusions, despite the similar design and patient population with ULMCA stenosis. In our opinion, these apparently contradictory conclusions can be attributed to several factors.

Full table

The conclusion of a trial is largely dependent on the preselected endpoints. Periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI) as an endpoint has been controversial due to its definition based on arbitrary enzyme release thresholds, which change from time to time. Besides, its value in representing clinical and prognostic differences between CABG and PCI remains unclear. NOBLE did not include periprocedural MI as part of its composite primary endpoint; however, EXCEL did. In fact, EXCEL adopted a new definition of periprocedural MI during the study (12), which was quite distinct from the contemporary Third Universal Definition of MI (13). Importantly, the non-inferiority of PCI compared to CABG demonstrated in the EXCEL trial was largely driven by periprocedural MI. Target vessel revascularization (TVR) has been widely used as an endpoint in the previous RCTs comparing CABG vs. PCI (1,4,5,8). However, EXCEL did not include TVR as part of its composite primary outcome (10).

The duration of follow-up in a trial is also critical to allow for correct interpretation of study data. NOBLE and EXCEL reported the 5- and 3-year follow-up results, respectively. The longer the follow-up time, the more likely the clinical or prognostic differences between CABG and PCI, if any, can be observed. Based on the previous studies, the slopes of event rates within the CABG and PCI groups start to diverge and reach statistical significance after 2 to 3 years of follow-up (7,8). NOBLE reported that CABG was superior to PCI at 5 years of follow-up (11), while EXCEL indicated PCI was non-inferior to CABG at 3 years (10). Moreover, the event slopes of CABG and PCI in EXCEL crossed at 3 years. It will be interesting to see the 5-year follow-up data in EXCEL. Furthermore, 29.1% of the EXCEL study subjects were diabetics, whereas NOBLE only had 15% diabetics. This might have contributed to the worrisome excess death signal (8.2% vs. 5.9%, PCI vs. CABG, respectively; P=0.11) in the PCI group in EXCEL.

As mentioned in the earlier section, previous RCTs consistently showed that the incidence of stroke was higher in CABG. However, there was no excess stroke signal observed in the CABG groups of both NOBLE and EXCEL. In fact, NOBLE demonstrated a trend of increasing stroke risk in the PCI group at 5 years [PCI vs. CABG: hazard ratio (HR) 2.20, 95% CI, 0.91–5.36, P=0.08] (11). This is thought to be due to improved pharmacological stroke prevention strategies in the CABG group, such as the more frequent continuation of dual anti-platelet therapy and statins both before and after CABG. It may also relate to more frequent repeat revascularization and vascular events/procedures in the PCI group.

Looking at these RCTs comparing CABG vs. PCI, we often forget a very important question: have we provided the best quality of CABG to compare with PCI? Surgeons should bear in mind that all of the above mentioned RCTs compared CABG with the most advanced stents at the time of the studies. Revascularization using arterial grafts have been proven to be associated with improved survival outcomes (14), superior long-term graft patency (15), and less MACE/MACCE (16). However, the utilization of arterial grafts in these RCTs was suboptimal. The proportion of patients who received total arterial grafting was only 24% and 2% in EXCEL and NOBLE, respectively. We as surgeons ought to work to optimize our surgical technique, in order to provide the best long-term results and uphold CABG as the gold revascularization standard.

The next big question: revascularization in patients with CAD and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction

At present, we have data regarding PCI vs. CABG in patients with complex multivessel CAD and diabetes (4,7). The data on left main disease is evolving, as discussed in the previous section (10,11). What remains unexplored is the patient population with CAD and left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction represents an increasing public health issue, with its incidence expected to rise steadily in coming years. To date, there has not been a RCT investigating the optimal revascularization strategy in this patient population. Moreover, this group of patients have been routinely excluded from the trials comparing CABG vs. PCI. Wolff et al. published a meta-analysis which included 21 studies involving a total of 16,191 patients (17). The authors concluded that revascularization, regardless of modality, was superior to medical treatment in improving survival in this patient population. When compared with PCI, CABG still showed a survival benefit (HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75–0.90; P<0.001). Nevertheless, these results are only hypothesis-generating and remain to be tested in future randomized clinical trials.

Conclusions

To date, RCTs comparing CABG and PCI have demonstrated the superiority of CABG in patients with multivessel CAD, specifically in terms of survival and MACE/MACCE. The recently published EXCEL and NOBLE trials have triggered tremendous discussion due to their apparently conflicting conclusions. There has been enthusiasm around revision of the current revascularization guideline based on the EXCEL trial. However, this is likely premature due to the controversial study endpoints, as well as short follow-up. Despite the well-demonstrated superiority and longevity of arterial grafts in CABG, their utilization in all the contemporary RCTs has been suboptimal. Future trials should focus on revascularization in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction. From the surgeon’s perspective and in light of rapid advances in PCI technologies in recent years, a collaborative effort is needed to continually improve our CABG techniques for better surgical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Rodriguez AE, Baldi J, Fernandez Pereira C, et al. Five-year follow-up of the Argentine randomized trial of coronary angioplasty with stenting versus coronary bypass surgery in patients with multiple vessel disease (ERACI II). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:582-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serruys PW, Ong AT, van Herwerden LA, et al. Five-year outcomes after coronary stenting versus bypass surgery for the treatment of multivessel disease: the final analysis of the Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study (ARTS) randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;46:575-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Booth J, Clayton T, Pepper J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of coronary artery bypass surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: six-year follow-up from the Stent or Surgery Trial (SoS). Circulation 2008;118:381-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2009;360:961-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kapur A, Hall RJ, Malik IS, et al. Randomized comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with coronary artery bypass grafting in diabetic patients. 1-year results of the CARDia (Coronary Artery Revascularization in Diabetes) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:432-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Serruys PW, Onuma Y, Garg S, et al. 5-year clinical outcomes of the ARTS II (Arterial Revascularization Therapies Study II) of the sirolimus-eluting stent in the treatment of patients with multivessel de novo coronary artery lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:1093-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2375-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park SJ, Ahn JM, Kim YH, et al. Trial of everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1204-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn JM, Roh JH, Kim YH, et al. Randomized Trial of Stents Versus Bypass Surgery for Left Main Coronary Artery Disease: 5-Year Outcomes of the PRECOMBAT Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2198-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stone GW, Sabik JF, Serruys PW, et al. Everolimus-Eluting Stents or Bypass Surgery for Left Main Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med 2016;375:2223-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Makikallio T, Holm NR, Lindsay M, et al. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in treatment of unprotected left main stenosis (NOBLE): a prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2016;388:2743-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moussa ID, Klein LW, Shah B, et al. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1563-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2007;116:2634-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taggart DP, D'Amico R, Altman DG. Effect of arterial revascularisation on survival: a systematic review of studies comparing bilateral and single internal mammary arteries. Lancet 2001;358:870-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaudino M, Antoniades C, Benedetto U, et al. Mechanisms, Consequences, and Prevention of Coronary Graft Failure. Circulation 2017;136:1749-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Locker C, Schaff HV, Daly RC, et al. Multiarterial grafts improve the rate of early major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in patients undergoing coronary revascularization: analysis of 12 615 patients with multivessel disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2017;52:746-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolff G, Dimitroulis D, Andreotti F, et al. Survival Benefits of Invasive Versus Conservative Strategies in Heart Failure in Patients With Reduced Ejection Fraction and Coronary Artery Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Circ Heart Fail 2017.10. [PubMed]