Robotic trans-atrial and trans-mitral ventricular septal resection

Background

Idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic septal obstruction (IHSS) is a site-specific form of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy or HOCM, whereby the aortic outflow tract becomes obstructed during systole by thickened, bulging septal muscle. Additionally, abnormal septal-anterior papillary muscle attachments may prevent normal leaflet and chordal motion, enhancing systolic obstruction. IHSS also can be complicated by a dynamically displaced anterior mitral valve leaflet, which during systole becomes closely apposed to the thickened ventricular septum by the Venturi effect. Problems arise not only from the increased outflow obstruction but also the consequent leaflet malcoaptation resulting in significant concomitant mitral insufficiency.

Septal obstruction is accentuated by exercise, inotropic infusions, ventricular under-filling and a reduction in afterload. Over time, even mild exercise induces symptoms of dyspnea and often arrhythmias. Sudden death can result from this condition. Generally, this condition can be diagnosed by echocardiography or cardiac catheter pressure measurements. Outflow tract pressure gradients can be increased diagnostically by induction of premature ventricular contractions or amyl nitrate inhalation. Current treatments include alcohol septal ablation, resynchronization pacing or surgical myectomy. Surgery has been shown to have the best long lasting results, especially in patients with very high pressure gradients.

Clinical vignette

A 65-year-old man developed progressive dyspnea to the point that he had stopped all exercise. At rest to moderate activity, he was considered to be in class II NYHA heart failure. He had no significant arrhythmias. Beta and calcium channel blocking drugs did not alleviate his symptoms. A transesophageal echocardiogram showed significant subaortic ventricular septal thickening with severe obstruction, significant systolic anterior motion (SAM) and moderate mitral regurgitation. At rest, the outflow tract pressure gradient was 80 torr and coronary angiography was normal. Additional gradient-enhancing perturbations were not carried out. A robotic septal myectomy was planned. After the operation, his aortic outflow flow tract gradient had reduced to 10 torr and his mitral regurgitation had decreased markedly. Thereafter, he remained asymptomatic. This patient’s preoperative transesophageal echocardiogram is shown in Figure 1.

Operative preparation

In the Atlas of Robotic Cardiac Surgery and other publications, we have detailed the anesthetic, cardiopulmonary perfusion, myocardial protection and set-up methods used for robotic mitral valve repairs (1,2). These preparations are exactly the same as for the operation described herein. Visualization of the mitral valve is the same; however, dynamic retractor manipulation is somewhat different than in a repair. Detailed pre-operative trans-esophageal echocardiographic studies are essential. It is important to determine the length of the anterior mitral leaflet as well as the point of exact apposition with the septum. Maximum and minimum septal thickness measurements help determine the proper depth of muscle resection, which we measure intra-operatively.

Surgical techniques

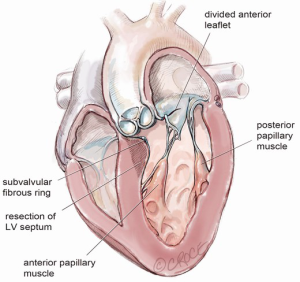

Mitral valve anterior leaflet detachment

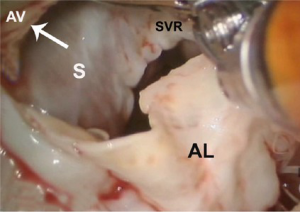

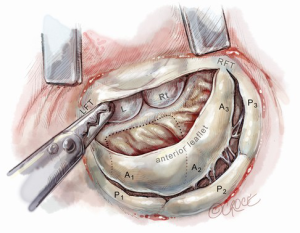

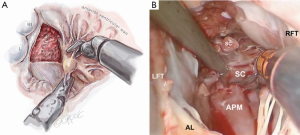

After exposure of the anterior leaflet using the dynamic robotic left atrial retractor, we generally begin our incision through the leaflet at the right fibrous trigone with curved robotic scissors, leaving a 2-mm rim of leaflet attached to the annulus. Thereafter, this incision is carried toward the left fibrous trigone, taking care not to injure the aortic valve leaflets. Without completely freeing the anterior mitral leaflet from the left trigone and commissure, the septum and anterior papillary muscle often become exposed. However, should exposure be inadequate, the anterior leaflet can be released from the trigone and commissure to ‘drape’ it out of the surgical field. Figure 2 shows where the anterior leaflet has been detached from the annulus, revealing the hypertrophied septum. Note the muscular attachments of the anterior papillary muscle to the septum. Figure 3 shows the hypertrophied septum rimmed by a whitish subvalvular fibrous ring. The latter results from the back of the anterior leaflet hitting the septum during systole. Figure 4 illustrates the planned area of septal resection in juxtaposition to the right and left aortic valve cusps.

Septal muscle resection

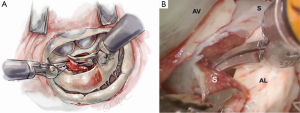

The aortic valve leaflets should be redefined, as the nadir of the right coronary cusp is the landmark for beginning the septal resection. At this time, administration of antegrade cardioplegia can help define the nadir of each aortic valve leaflet. The fibrous subvalvular ring should be resected first. We plan the depth of our septal resection from the trans-esophageal echocardiographic study. The rectangular septal resection should be commenced at the nadir of the right aortic valve cusp and continued in a counterclockwise direction, toward the left fibrous trigone and away from the interventricular conduction bundle, which resides in the region of the non-coronary cusp (Figure 5). This visual orientation is critical as it is the reverse of that seen through the trans-aortic approach to the septum. The resection should be continuous from the base of the aortic valve cusps to the base of the anterior papillary muscle. It is essential to remove sufficient septal muscle. We confirm the depth of this resection using a small millimeter ruler.

Anterior papillary muscle mobilization

The septal resection must be carried to the anterior papillary muscle base, which should now be adequately exposed. Generally, this pathology is associated with muscular septal connections that extend to the base of the anterior papillary muscle. These muscular bands keep the anterior papillary muscle positioned either in or near the outflow tract. This position alone may promote a higher gradient and tendency to develop preoperative SAM. All of these connections should be divided down to the papillary base (Figures 2,6). This allows posterior displacement of the anterior papillary muscle, transposing the associated chordae tendineae and leaflet away from the septum during systole. If necessary, the papillary muscle can be mobilized even more and sutured to the posterior papillary muscle. This may help to decrease outflow obstruction and reduce the chance of postoperative SAM. Occasionally an accessory papillary muscle is attached to the posterior region of the anterior leaflet and should be resected along with any abnormal chordae tendineae.

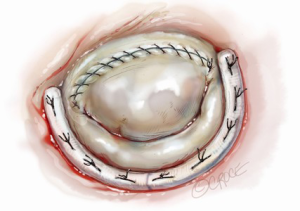

Anterior mitral leaflet re-suspension and annuloplasty

After completing the septal resection with papillary muscle mobilization (and possible relocation), the anterior leaflet should be re-suspended to the 2-mm residual leaflet rim using a 4-0 PTFE suture. We prefer to use PTFE suture material as there is less chance of breaking it with the robotic instruments. Generally, we start with a suture placed at the right fibrous trigone to visualize and avoid injury to an aortic valve cusp (Figure 7). Alternatively, one can place a suture at each trigone and these can be directed to converge at the mid-anterior leaflet, where they are tied. Often the anterior leaflet has been altered pathologically from the trauma of repeated septal coaptation. Any adherent anterior leaflet fibrous tissue should be removed to provide better mobility. If the anterior leaflet has been shortened either by the intrinsic pathology or potentially during re-suspension, a pericardial patch should be interposed between the annulus and cut leaflet edge. This allows more leaflet billowing away from the septum and decreases the risk of residual SAM. We complete the valve repair with a flexible band annuloplasty (Figure 8). This allows leaflet coaptation and free movement without significantly reducing the distance between the septum and lateral annulus. We do not recommend using a complete annuloplasty ring in these patients.

Results and pitfalls

For patients with severe septal hypertrophy, a long anterior mitral leaflet with pre-existing SAM or a small aorta or aortic annulus, we prefer the robotic trans-mitral approach. In carefully selected patients we have had attained excellent post-resection outflow gradients and no significant SAM. Generally, visualization is superb and this helps to avoid complications such as the development of heart block, a ventricular septal defect or an aortic valve injury. To avoid these pitfalls, surgeons must orient themselves to a different visual topographic landscape than seen in the trans-aortic approach (3). By guiding the depth of the septal resection using trans-esophageal echocardiography and staying away from the membranous septum, a ventricular septal defect can be avoided. In addition, the risk of heart block can be minimized by beginning the septal resection at the nadir of the right aortic cusp and continuing it toward the left fibrous trigone. A hypertrophic anterior papillary muscle can supplement outflow tract obstruction, and muscular attachments to the septum must be divided (4). This should allow free motion of chordae tendineae and anterior mitral leaflet away from the septum during systole. Should residual SAM occur after a generous resection, the anterior leaflet can be lengthened with a pericardial patch to enable billowing and optimal flow from the outflow tract. As a last resort, residual SAM can be corrected using the Alfieri leaflet edge-to-edge method. Mitral valve replacement is a much less desirable way to correct residual SAM and should be avoided.

Comments

Braunwald et al. [1960] first detailed the clinical manifestations as well as the hemodynamic and angiographic findings of IHSS (5). Thereafter, Morrow developed his well-known trans-aortic valve approach to perform a generous interventricular septal resection, which has remained the gold standard for treating IHSS (6). Operative complications have included heart block, ventricular septal defect formation, aortic valve injury and residual SAM. In 2002, Casselman and Vanermen endoscopically performed a septal myectomy for IHSS via a left atrial approach (7). They incised the anterior mitral leaflet base (aorto-mitral curtain) to expose and resect the hypertrophic interventricular septum. Mohr also described another trans-atrial approach to this pathology by re-suspending the anterior mitral leaflet with PTFE loops (8). Based on our extensive mitral valve repair experience with the daVinci tele-manipulation system, we developed a robotic trans-mitral method to perform a generous septal resection, combined with papillary muscle release or repositioning (2). The superior magnified 3D visualization with this system combined with enhanced ergonomics enables us to work with the greatest facility in this subvalvular space. We believe that it provides the surgeon with a wider and more accessible workspace than the trans-aortic approach.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Wiley Nifong and our robotic team at the East Carolina Heart Institute made possible the development of this operative technique.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Nifong LW, Rodriguez E, Chitwood WR Jr. 540 consecutive robotic mitral valve repairs including concomitant atrial fibrillation cryoablation. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:38-42; discussion 43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chitwood WR. Idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic septal obstruction: Robotic trans-atrial and trans-mitral ventricular septal resection. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;17:251-60. [Crossref]

- Schaff HV, Said SM. Transaortic extended septal myectomy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Oper Tech Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;17:238-50. [Crossref]

- Redaelli M, Poloni CL, Bichi S, et al. Modified surgical approach to symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with abnormal papillary muscle morphology: Septal myectomy plus papillary muscle repositioning. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:1709-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braunwald E, Morrow AG, Cornell WP, et al. Idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis: Clinical, hemodynamic and angiographic manifestations. Amer J Med 1960;29:924-45. [Crossref]

- Morrow AG, Reitz BA, Epstein SE, et al. Operative treatment in hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. Techniques, and the results of pre and postoperative assessments in 83 patients. Circulation 1975;52:88-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casselman F, Vanermen H. Idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis can be treated endoscopically. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;124:1248-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mohr FW, Seeburger J, Misfeld M. Keynote Lecture-Transmitral hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) repair. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:729-32. [PubMed]